The enchanting glow of Piazza del Popolo, casting its radiance upon the tables where Canova, Federico Fellini, and Italo Calvino once convened to discuss a cinematic endeavour destined to remain unrealised. The ephemeral title of their project danced whimsically, embodying an affectionate reverence for the Bel Paese and an overarching aspiration – “Visioni d’Italia.” Celebrating Calvino’s centenary of birth this October, it is worth noting that their collaboration spanned over two decades, with Calvino earnestly desiring a rendezvous in the heart of Rome.

In 1963, during a breakfast meeting in Piazza del Popolo, the seeds of an enduring friendship between these two towering figures of the 20th century were sown. Calvino, a well-established author known for his “Trilogy of the Ancestors” and a treasury of two hundred Italian fairy tales, had taken the initiative to write a letter to Fellini, lavishing praise upon him for his magnum opus, “8½.” On the other side of the table sat Fellini, who had embarked on his cinematic journey in the 1950s with “Variety Lights.” Within the ambit of “Visions of Italy,” Calvino aspired to infuse a piece of his soul and envisioned a screenplay that would depict the nation as if it were “Kublai Khan’s pleasure palace.”

The friendship between Calvino and Fellini flourished, yet it faced a momentary rift when Calvino’s “The Nonexistent Knight” was published in 1959, marking the conclusion of the Ancestors Trilogy. At that juncture, Fellini had expressed a keen interest in acquiring the rights to adapt the novel into a film. However, Calvino, harboring reservations, declined the proposal and instead encouraged his agent to present it to Ingmar Bergman. Ultimately, neither Fellini nor Bergman would undertake the project, as Pino Zac would ultimately bring Calvino’s novel to the silver screen.

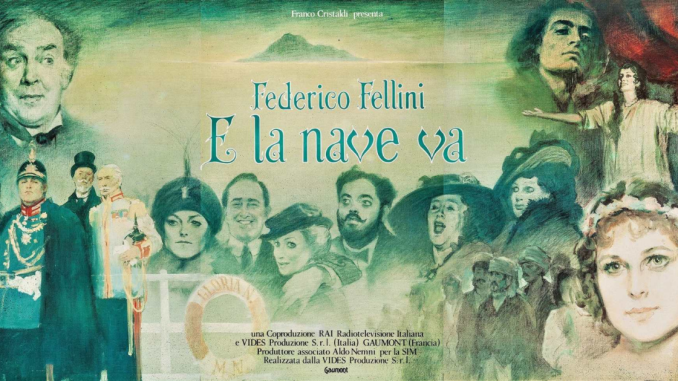

As they returned to the ambitious project of adapting Italian fairy tales, they were confronted with the challenge of weaving them into a cohesive narrative. After two decades of pondering this predicament, they finally uncovered a solution. Rather than a traditional narrative thread, they conceived a scenographic device akin to a playful board game, a creation emblematic of Calvino’s imaginative genius. This revelation occurred in 1983, while Fellini was engrossed in the making of “E la nave va,” and he envisioned enlisting his film’s technical team to craft this whimsical framework.

Yet, just two years later, Calvino departed from this world, leaving behind a void in their creative endeavour. Today, among the scant vestiges of this unrealized project are the marked passages and annotations within the pages of the two volumes of Italian fairy tales, discovered within Fellini’s private library at his study on Corso Italia.

Be the first to comment